Are Female Shōnen Mangaka a Guest in the House of Shōnen?

- Shan Freemoor

- Dec 4, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Dec 23, 2025

Senior Journalist -

Several months ago, I saw a few comments from men discussing Kei Urana, the creator of Gachiakuta, getting in her feelings after some male fan called her series “mid” (meaning average, mediocre, or just okay, rather than bad or terrible). She reportedly responded in a somewhat slanderous way, which some viewed as emotional. Certain men in the community felt this was typical female behavior instead of using the criticism as motivation to improve, as creators like Akira Toriyama or Masashi Kishimoto have said fan feedback often does, because that’s how males operate. Men tend to give blunt criticism to inspire growth, especially in spaces aimed at a male audience. So, should she and other female mangaka who choose to create Shōnen (stories centered around young male perspectives) accept such opinions as part of being “guests” in the house of Shōnen, rather than feeling they inherently deserve their place simply by achieving success there?

Yes, we know this is all entertainment, but these stories also have morals and perspectives for men to relate to and understand when a male is the protagonist. Can a woman truly tell a male perspective for a young male to understand the journey into becoming a man in their fantasy? The journey of understanding what a hero, not a heroine, truly looks like from a male perspective. Can a woman truly give a male rite of passage in a story?

For those who don’t know, forgot or try to detach what Shōnen is or means, Shōnen is a genre of manga that targets the interest of young males and young male teens created by male mangaka. Because who better to tell a male’s perspective and interest than a man who was once a young male and teen.

When it comes to Shōnen, more fans today seem thrilled with unorthodox themes that break Shōnen tropes, the art style and something to cosplay, and representation, especially in the West. The hot new thing is what’s different and inclusive. Are these fans, especially male fans, just new age and eccentric? Remember, these are just questions, not insults.

You see a lot of men today saying that women write better Shōnen for young males than men. Do women truly write better Shōnen, which is for young men by men, better than men? Or do we just have a new generation of eccentric men who just want to praise the novelty and emotionally charged series today? Remember, most Female mangaka protagonist are males, and they are telling his story from a supposed male perspective. There are some male fans on the internet who say can spot when a "male prespective and interest" series is done by a woman based on things like:

Very insecure, doubtful male protagonists or deuteragonists in moments that are uncalled for or make no sense, and their realization of their courage and confidence not being realistic or relatable to masculine male resolve.

No long, hard-earned training arcs. Instead, their newfound strength or abilities emerge from sudden emotional surges, dramatic realizations, or desperate attempts to protect those they love.

Very emotionally charged moments that feel out of place.

Moments lost that should have had responses from a male’s perspective.

Constant internal monologue, as if males think that much in their heads as females.

Mostly stoic, aggressive and/or masculine female deuteragonists or support that aren’t married to the male protagonist and who keep putting him in his place.

Female supporting characters oddly more powerful than the MC or male characters at times, even when those male characters are said to surpass them.

Borderline “incest-adjacent” brotherly love that female mangaka weirdly show or just the obsession with brother relationships.

Over-exaggeration and awkward of male bonding through punching and beating on each other.

Women like Rumiko Takahashi with Inuyasha, Kazue Kato with Blue Exorcist, Yana Toboso with Black Butler, Katsura Hoshino with D.Gray-man, Hiromu Arakawa with Fullmetal Alchemist, and now Kei Urana with Gachiakuta all have a lot of the elements mentioned. Elements you wouldn’t find most men doing or including.

For example, in Blue Exorcist: Kyoto Saga, season 2, episode 10, when Rin Okumura couldn’t unsheathe his demon sword in the middle of needing to protect himself and his friends, the constant inner monologuing of emotional doubt was frustrating as a guy. It took an emotional conversation with Suguro Ryuji about needing to win, hanging out with his friends, and him wanting to see Kyoto Tower, in the middle of a sudden-death battle, just to unsheathe it.

Or the constant emotional spazzing and inner monologue about himself and his purpose that Yukio Okumura did, which made you want to say, “Stop being a jealous, emotional b#t%h boy and accept reality.” Sephiroth from Final Fantasy VII had a better break with his reality than Yukio did.

Again, most female Shōnen mangaka protagonist are males, and they are telling his story from a supposed male perspective.

Are other modern male mangaka tagging along with many of these different but new tropes because they see they’re selling with audiences today because the males have drastically changed, wanting things more equality balanced? Hot butt kicking aggressive female, self-conscious and emotionally charged male characters.

And even if female Shōnen mangaka do a good job of telling a story from a male perspective, are they receiving help from male editors to change this or that? Editors are essential for manga creators; they can push dozens of changes to help a series better connect with the audience. Editors can save a manga series, as demonstrated by the case of One Piece, which helped revive Shōnen Jump magazine when its sales were declining. When a magazine is struggling, an editor can champion a new series that becomes a runaway success, boosting overall sales and readership. Editors also work with the artist to refine the story, art, and pacing to ensure it’s the best it can be, which can be crucial for a series’ longevity and quality. Editors can influence the direction of a story, like suggesting a tournament arc instead of a world-traveling one for Naruto, a decision that significantly shaped the series.

![Kazuhiko Torishima, a legendary Shueisha editor known for his work on iconic series like Dr. Slump and Dragon Ball, helped shape the success of many major titles including One Piece, Naruto, and Bleach, making him one of Japan’s most influential manga editors.]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/89b7eb_d3afa86a86b541ae925141f081592eb3~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_620,h_413,al_c,q_80,enc_avif,quality_auto/89b7eb_d3afa86a86b541ae925141f081592eb3~mv2.jpg)

Most female Shōnen mangaka work with notable editors, typically male, within major publishing houses because for a third time, most female Shōnen mangaka protagonist are males, and they are telling his story from a supposed male perspective. Shunsuke Motegi was Takahashi's last editor on Inuyasha and her first editor on Kyokai no RINNE. Hiromu Arakawa, worked closely with the editorial office, even locking herself in the office for two days to work on storyboards for a crucial chapter of Fullmetal Alchemist.

This may seem like a contradiction to what was previously stated about female Shōnen mangaka including certain elements in their stories when the editor is male, and changing aspects that don’t align with a male’s personality or perspective. But life is not full of contrasts alone. There may be elements that the female Shōnen mangaka wants in the story because she feels they are essential to the character or story’s resolve, growth, and continuity, so the editor approves them. An editor’s job is to help bring the mangaka’s vision to life as polished as possible, making only certain exceptional changes that don’t throw off the story. Many of these approved elements are the very traits that female Shōnen mangakan tend to exhibit in their work.

So are these women getting major help to write from and for a male’s perspective by their editors? Do we just have a group of eccentric, sensitive, and emotionally driven males now, to where it’s made it comfortable for female mangaka to come in and tell whatever story they want about men?

Have male shonen mangaka over the last 60 years been giving female mangaka the tools—whether through tropes, character archetypes, concepts, styles, personal mentoring, editorial help, and so on—to enter this space and imitate the male perspective in order to cater to and capture the attention of a male audience makes them better at it? The same can be said of male creators working in shojo, which is a point I address later.

The backlash from this question

Don’t be surprised to see a lot of backlash from this question by both males and females, some to the point where you’ll know they didn’t read the entire article. With that, are we seeing manipulation in the form of fan support where, instead of being given the approval of being in a male space to tell a male-perspective story, some people are being compelled to celebrate it in a tokenized way, where women are seen as dominating male spaces and better than them, and if you don’t accept it or don’t see them as equal in telling that perspective, you’re labeled sexist or misogynist? Or their favorite line, “incel”? Males, and even females supported by progressive liberal males, may be gatekeeping this new eccentric perspective of what the male perspective should look like today.

Are young men being persecuted and compelled into being eccentric in their thinking, instead of being able to rest in their masculinity with their thoughts, feelings, and perspectives on a series they may feel doesn’t completely relate to them, felt weird at certain points, or felt mid? Because if you let them tell it, even speaking on this is toxic masculinity—anything that doesn’t fully accept strong and unconventional emotions or females in male spaces.

I would like to ask the naysayers of this article this: if this was truly targeted for everyone, why even have categories? Why can’t a female mangaka telling her fictional action or combat story from the male character's prespective just drop her series in Shojo or Josei if it’s really not about male or female content? Why can’t it be dropped on the front cover of these shojo magazines?

Because they know that most female readers don’t like all that fighting, feat displays of power, or heavy male-driven perspective stories.

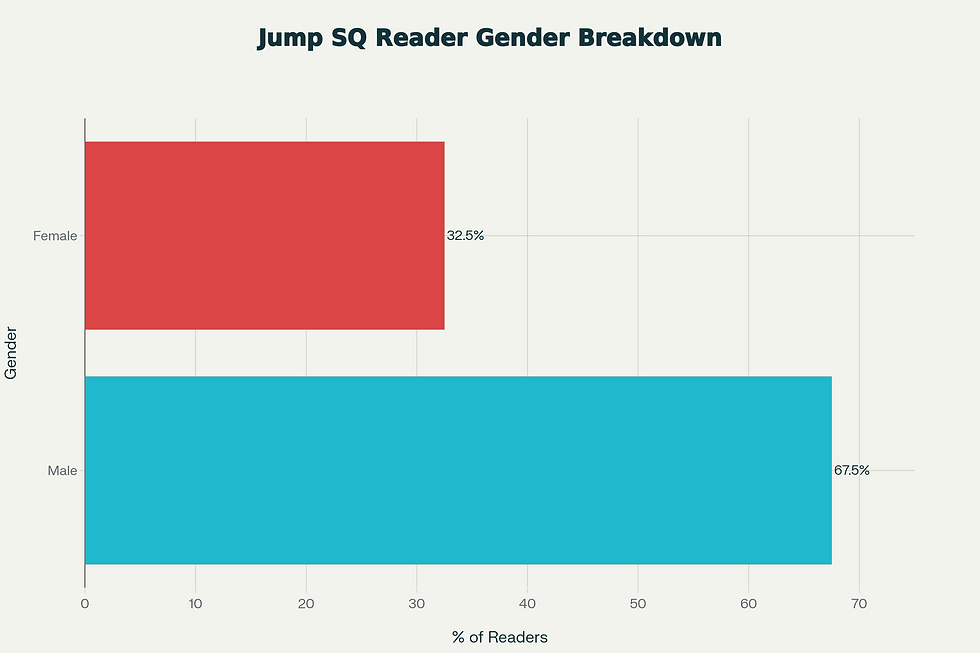

Shueisha’s Jump SQ. (a Shōnen/semi-seinen magazine) reports about 67.5% male and 32.5% female readers. Another Japan-focused survey that sampled adults across age groups reported that about 75% of respondents watch anime, with middle‑aged males identified as the leading demographic, and a higher proportion of females than males saying they do not watch anime at all.

There are also claims that Weekly Shōnen Jump now has something close to a 50/50 split between female and male readers. Do you think this is due to the fact that a lot of female characters in manga are extremely strong and empowered, with great cosplay appeal to where females feel more comfortable finding interest in it? You can definitely say that a lot of Shōnen female characters today fit perfectly into the Western feminist movement idea of strong, tough, aggressive, independent, empowered characters who can hold their own against the men in the series, even when those men are big, powerful brutes.

Here’s the question on the flip side: would a male mangaka in shoujo not be a guest in that house as well? Or would he be known for writing for young and teen females better than a woman? One survey in 2021 found that around 77% of mangaka in general are female, although the survey’s sample size may limit its generalizability. Shoujo manga is a demographic primarily targeted at adolescent girls and women, and readership heavily skews female, with one survey indicating that roughly 85% of readers were female compared to 15% male. This means female mangaka are successfully telling stories from a female perspective and interests because the number of female readers is substantially higher. So what’s happening with the stories in shonen and even some seinen to where that number is tipping? Is it the eccentric male storytelling with empowered female characters that’s making women feel comfortable to read, where the numbers are tilting or becoming even?

I’ll say this for the final time… Most shonen female mangaka protagonist are males and they are telling his story from a supposed male perspective.

The reason for presenting these statistics about men’s and women’s interests in shonen and shojo is to ask: what is happening that makes many women feel comfortable crossing over into shonen, whether as readers or creators, while men often do not feel similarly comfortable crossing over into shojo as readers or creators? Are men simply more accepting, more gynocentric in their thinking, or more willing to encourage women to enter these spaces and tell stories about a male perspective from a female point of view?

So instead of getting mad and thinking this is a sexist, male‑chauvinistic article or any other ad hominem you can throw at me for just asking questions, step out of your emotional box and answer the question. Could a woman truly write an epic male rite‑of‑passage story for a man to truly feel like a man? Can a woman really tell a story from a male perspective that truly resonates with a predominantly male audience? Or are we just seeing, again, the development of an eccentric generation of very emotionally driven and sensitive sided men who accept any or every alleged male perspective story as the new and true masculinity?

Why would it not be acceptable to ask whether female shōnen mangaka are “guests in the house of shōnen”? Are Eminem or MGK not guests in the house of hip-hop, a predominantly Black-cultured musical space rooted in struggles and perspectives from which they themselves took the blueprint? It is similar to an American claiming they cook Japanese food better than a Japanese person when their knowledge of the cuisine comes from the Japanese in the first place. Are they not guests in the house of Japanese cuisine? Would a heterosexual man be considered a guest in the LGBTQ community if he attempted to tell a story from what he believes is their perspective (in the West, he would probably be called “closet gay” for doing so)? Would foreigners who dress and speak in Japanese style still be considered guests (gaijin} in Japan by the Japanese? The answer to the gaijin question is a definite “yes” according to most Japanese people.

What is the point to all of this?

In a world where many believe these things should unfold in a neat, perfect-world spectrum, it’s worth remembering this: stepping into a space that isn’t fully yours is a privilege, not a right. Enter it with humility, gratitude, and reverence. Recognize that being allowed to tell a story from a perspective you can never fully live is an honor, not an entitlement. And never forget to humble both yourself and the audiences who insist you can speak more authentically than those who embody that experience every day even within the highest reaches of fiction. Sometimes the truest strength lies in acknowledging the limits of our own understanding.... .Or am I wrong?

So I ask, one last time: Are female Shōnen mangaka merely guests in the house of Shōnen (a space shaped by male perspectives), or should they need no invitation at all, sometimes even surpassing their male counterparts in telling stories about young males and teens?

Comments